AI-powered Roll-ups - Part III: Are they VC-scale?

Definitions and Approach

In Parts I & II of this series, we built a framework to identify industries best suited for AI-powered roll-ups and established that the venture debt market is primed to support such endeavours. But what about equity markets? What types of equity investors are best suited to fund these ventures?

Specifically, I'm trying to determine whether AI-powered roll-ups could qualify as VC-scale investment opportunities. Before we begin, how do we define VC-scale? For this article, we'll define it as:

"if things go according to plan, is there a reasonable chance of achieving a 10x return?"

I'm mindful that this definition might stir debate, with VC purists insisting only potential 100x returns qualify (a logic I fully understand and respect). But let’s stick to the 10x definition for now.

For me, the simplest approach is to simulate how such an opportunity could unfold. By modeling various scenarios, we can identify which could realistically yield that 10x return. It’s a simplistic model designed to provide directionally accurate insights—not precise calculations down to the nth decimal.

You can download the model here, and run your own assumptions.

In the remainder of this article, I'll walk you through my findings and discuss the implications for both investors and builders in this space—crucial to set realistic expectations for both parties.

But first the tl;dr answer:

Yes, achieving 10x returns is possible—but *Conditions apply

Forecasting the financials of an AI-powered roll-up

Let's start by exploring one likely scenario to familiarize you with the model.

You can download the full model here

Here are the key assumptions and rationale. While there are numerous smaller assumptions, these are the pivotal ones:

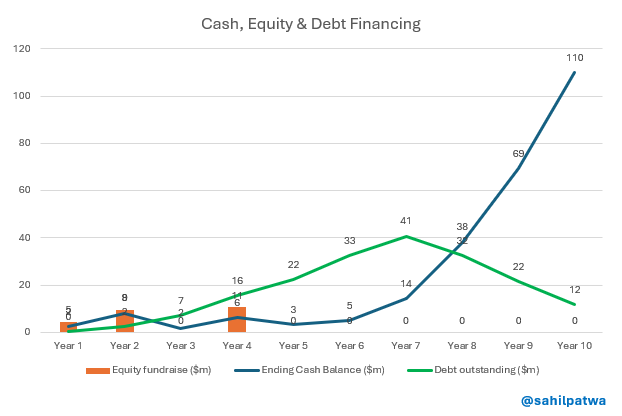

Building these assumptions out over ten years, you can achieve a $500M+ ARR, ~$70M EBITDA business generating very healthy cash—impressive! Remarkably, if executed correctly, this can be accomplished with less than $50M in equity investments.

The Seed, Series A, and Series B investment amounts were calculated to provide sufficient runway (1.5-2 years, with buffer) covering HQ, debt servicing, and acquisition expenses.

As evident, this scenario offers a 10x opportunity for Seed investors, though less so for Series A and B. I ran numerous such simulations to determine if realistically achieving 10x returns is even feasible - and if yes, what does it take?

What does it take to achieve 10x+ for Seed, Series A & Series B investors?

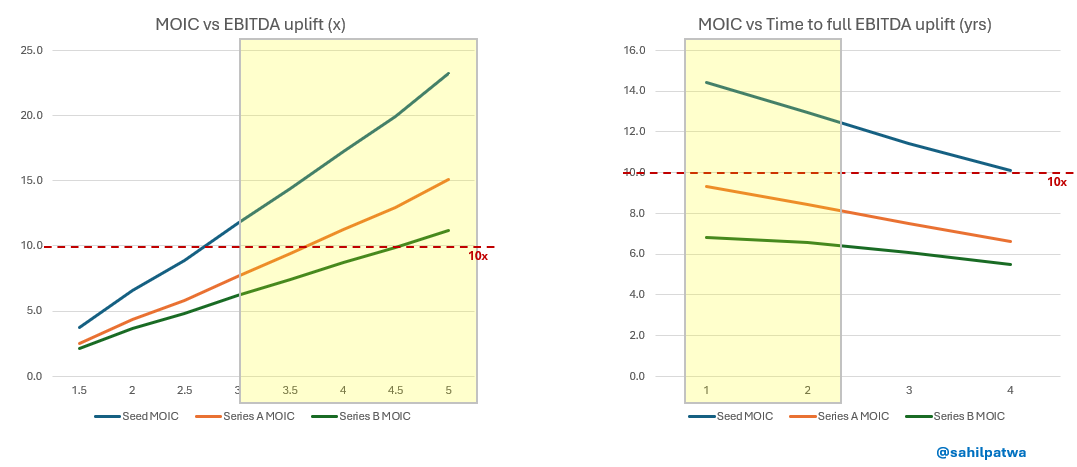

1. Potential for 4-5x EBITDA uplift in 2-4 years:

As shown below, a 4x+ EBITDA uplift is nearly essential for targeting a 10x outcome. Even at a 2-4x uplift, the business case remains compelling, though returns for Series A investors onwards may range closer to 5-8x.

The speed of achieving this uplift significantly impacts returns—the quicker the uplift, the sooner cash becomes available for subsequent acquisitions, thereby amplifying investor leverage.

Naturally, achieving this uplift is easier if the initial EBITDA percentage is low (3-8%). Nonetheless, it's crucial to validate upfront that a 4x+ uplift is feasible. And this is not fiction, I have seen those kinds of AI-powered bottomline boosts happen at several companies (if you’re curious to know the details, ping me separately and I’ll tell you 😉).

Also, remember - these uplifts are what justify R&D spending at the HQ level!

Another implication of this, is that when faced with a choice, focus on achieving EBITDA uplift (even at the cost of delayed next acquisition) - and prioritize acquiring good quality assets where path to uplift is relatively clear over assets that you might get at a cheaper multiple.

2. Fewer equity rounds but higher dilution per round than typical VC deals:

Plan for 3-4 financing rounds through exit—no more. Eventually, cash flows, additional debt capacity, and seller financing/earn-outs should fund new acquisitions. Using venture funding for early R&D and initial proof-of-concept acquisitions makes sense; funding stagnant companies at 5% EBITDA does not.

Given significant early equity goes into acquisitions, valuations shouldn't follow typical VC multiples (10x revenue = fail). Expect 25-30% dilution per round for economics to work for VC investors (still leaving founders and management 30-50% equity).

3. HQ costs must stay nimble:

This is crucial, especially early, when capital must stretch between R&D and acquisitions. This balance is delicate; Series A investors seek proof that founders can acquire companies reasonably and achieve substantial EBITDA uplifts.

As the company scales, HQ overhead can easily balloon—this can undermine strategy. Aim for HQ costs to grow sub-linearly relative to revenue. Staying nimble accelerates profitability, unlocking cheaper debt financing (see Part II). If there's ever a place to stretch a dollar, this is it.

4. Founder profiles are critical:

A founding team with strong industry, operational, tech, and M&A expertise can secure larger seed rounds, enabling greater early investment in R&D or more significant initial acquisitions.

As detailed in Part II, strong founder profiles also unlock venture debt earlier, adding non-dilutive capital cushion in early stages. The underlying assumption: strong teams will execute effectively, turning Excel models into actual returns.

5. Don't rely on multiple-expansion:

I have started seeing financial models assuming acquisitions at 3-4x EV/EBITDA, exiting at 6-7x, even 10-12x multiples. While scale can lead to higher multiples, remember: multiple expansion is the cherry on top—not the sundae itself! As a general rule, I never factor any multiple expansion into my projections.

And there’s a practical explanation for this: acquisition multiples naturally rise as assets grow larger, with significant revenue coming from later, higher-multiple acquisitions. The scenarios below—constant multiples versus expanding multiples—show nearly identical outcomes (numbers sometimes align beautifully!).

Another subtle but important point to consider here, is the longevity of EBITDA uplifts. The simulation assumes consistent EBITDA uplifts even in later acquisitions (6-7 years down the road). If competitors catch up technologically, price competition may erode EBITDA gains. Hence, choosing industries where competitor catch-up potential is low (covered in Part I) is essential.

Finally, I'd like to re-emphasize that numerous assumptions underpin this analysis. A huge thanks to everyone who shared their valuable insights - the model’s strength depends entirely on the quality of these inputs. And if you have any additional perspectives or suggestions, please reach out via Twitter/email/LinkedIn—I look forward to incorporating your feedback in future updates.